A control system is a mechanism — mechanical, biological, or otherwise — that forces a measure towards a reference. One example is a thermostat. You set the desired temperature of your house to 73 degrees Fahrenheit, and the thermostat springs into action, to get its reading to 73 °F or die trying.

The usual assumption is that a control system works like a target, and tries to correct deviations from that target. Take a look at the simplified diagram below. In this case, the control system is set to the target indicated by the big arrow, at about 73 °F. Since control is less than perfect, the temperature isn’t always kept exactly on target, but in general the control system keeps it very close, in the range indicated in blue.

However, there are other ways to design a control system.

One way is to make a single-headed control system, that has a reference level, and simply keeps the measure either above or below that level. For example, this single-headed control system is designed to keep the temperature above 70 °F:

This is how early thermostats worked, and how many still work in practice. They do nothing at all until the temperature drops below some reference level, at which point they turn on the furnace, driving temperature upwards. Once the temperature returns above the reference level, the furnace is switched off. Barring any serious disturbances, this keeps the temperature in the range indicated in blue.

This works fine if your house is in Wales or in Scandinavia, where things never get too hot. But what if you want to control the temperature in both directions?

Easy. You just add a second single-headed control system on top of the first one, controlling the same signal in the opposite direction. This is a double-headed control system, that keeps the signal between two reference values:

One “head” kicks in if the temperature gets too low, and takes corrective actions like turning on the furnace. The other kicks in if the temperature gets too high, and takes corrective actions like turning on the air conditioning. Together they form a larger control system that, barring any damage or huge disturbances, keeps the temperature in the range indicated in blue.

(Both “single-headed” and “double-headed” are terms of our own invention. There may be official terms for these concepts in control engineering. If so, we haven’t been able to find them. We would love to hear if there are existing terms, please let us know!)

There is some reason to think that biological control systems in animals are mostly double-headed. This is due to the fact that these control systems are built out of neurons, and neural currents are in units of frequency of firing. Unlike other signals, frequency of firing can’t be negative: the number of impulses that occur in a unit of time must be zero or greater.[1]

Obesity

The current scientific consensus on obesity (link, link, link, link, link) is that it is the result of a problem with the control system(s) in charge of regulating body fat, the set of systems sometimes called the lipostat (lipos = fat).

We can explore this idea through a few examples. For the purposes of illustration, let’s use BMI for our units. BMI isn’t perfect as a measure — obviously your nervous system doesn’t actually measure its weight by calculating BMI — but it’s a simple and familiar number that will do the trick. In general we should make it clear, all the following examples are greatly simplified. In reality, the body seems to have many control systems to regulate body weight, not just one.

For starters, we know that the lipostat can’t be single-headed, because with ready access to food, people don’t generally starve to death, nor do they become fatter and fatter until they burst.

Clearly body weight is controlled in both directions. This means it’s a double-headed system. One part of the lipostat keeps you from getting thinner than a certain threshold. And another, separate part of the lipostat keeps you from getting fatter than a different threshold.

On to the examples. A person with a healthy lipostat would look something like this:

The two heads are set to different points, leaving a bit of room between the upper and the lower thresholds. This person’s weight can easily wander between BMIs of about 20 and 23, pushed around by normal behavior. But if they go above that upper limit, or below the lower limit, powerful systems kick into play to drive their weight back into the blue range between the two heads of the system.

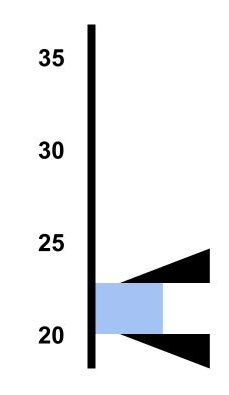

What about someone whose lipostat is not healthy, someone who has become obese? One way for this to happen is for both heads to be pushed to higher thresholds, like so:

Here you can see that the upper head has been set to a BMI of about 35, and the lower head to a BMI of about 31. As before, their weight is mostly free to wander between those two levels. If they’re trying to lose weight, they can probably push their BMI down to 31. But it will be very hard to push it past that point, since the lipostat will resist them vigorously. After all, the lower limit is designed to keep us from starving to death, so it has a lot of power behind it.

On the other hand, this person basically doesn’t have to worry about their BMI climbing above 35, since the upper limit is also defended. As long as their lipostat isn’t disrupted any further, they will remain within that range.

However, the heads don’t have to move together. They are at least somewhat independent systems, with separate set points. So another way to become obese is like this:

This person still has a lower limit of BMI 20, just like the healthy person in the first example. But they have an upper limit of BMI 35, as high as than the obese person in the second example!

This person is sometimes obese. On the one hand, unlike a person with a healthy lipostat, there’s nothing to keep this person’s weight from drifting up to a BMI as high as 35. So if they’re not “careful”, if they eat freely and without particular attention, sometimes it will.

But on the other hand, there’s nothing keeping this person from driving their BMI as low as 20, by doing nothing but eating less and exercising more. They don’t risk hitting a starvation response until they are well into the healthy BMI range, so they have little difficulty losing weight when they want to.

Lots of people find it really hard to lose weight. But you also encounter a lot of people who say things like, “when I was overweight I just decided to lose some weight, counted calories for a while, and made it happen, and it wasn’t that hard.” The double-headed model may explain the difference. Calorie-counters who sometimes drift upwards but can easily lower their weight on a whim have an altered upper threshold but a healthy lower threshold, while everyone else has had both their upper and lower thresholds pushed to obese new set points, and they face massive biological resistance when they try to return to a lower BMI.

Slightly Complicated

Our friend and colleague ExFatLoss likes to describe obesity as a slightly complicated problem. No one has solved obesity yet, but it doesn’t seem totally chaotic, so maybe there are just a few weird things that we’re missing. We agree that this seems likely, and one way that obesity could be slightly complicated is if different things are causing changes to the thresholds of the upper and lower heads of our lipostats.

To take a traditional example, perhaps eating lots of sugar raises your upper threshold, and eating lots of fat raises your lower threshold. In this model, if you eat lots of sugar but not lots of fat, your weight might drift up, but you can still control it. If you eat lots of fat, your weight is pushed up and can’t be pushed back down.

To take an example that seems more plausible to us, maybe one contaminant raises the upper threshold of your lipostat, and a different contaminant raises the lower threshold. Perhaps phthalates raise your upper threshold. This wouldn’t be very noticeable by itself, because you could still control your weight with diet and exercise. But maybe on top of that, exposure to lithium raises your lower threshold. This would keep you from pushing your weight back down. In combination, exposure to both contaminants would force you into obesity. (We should stress that this is a hypothetical, we have no idea whether these particular contaminants affect one head, or both, or neither.)

So much for things being slightly complicated. One way that obesity could be very complicated is if there are not just two heads, but lots of them, maybe dozens. This is almost certainly the case. Biology tends to be massively redundant, so the most likely scenario is that the body has several different ways of measuring your body fat, and each of these measures probably has its own control systems. So you probably have many “upper” and “lower” thresholds, all interacting. It might look something like this:

In this case, there are five heads making for five thresholds. The black thresholds have been forced wide open, defending a healthy lower BMI but a pretty high upper BMI. The red threshold is an additional lower defense, trying to keep BMI above 21. And the white thresholds are fixed to defending a range that’s solidly overweight to obese. This person is most likely to end up somewhere in the range that’s darkest blue, but could see movement all over the place. They won’t face serious resistance unless they try to push their BMI above 35 or below 20. But anything that raised the set point for that red threshold or the bottom black threshold would seriously limit their ability to stay lean.

Again, even this more complicated example is probably an oversimplification. While these models are good for illustration, real biology almost certainly involves more than 5 heads, defending lots of different thresholds in many different ways.

There is at least one other way in which a person could become obese. As before, you could set the lower limit quite high, say to keep a person’s BMI above 31. Then you could set the upper limit below the lower limit, like so:

The behavior of such a system is left as an exercise for the reader.

[1]: The systems engineer and control theorist William T. Powers explains this idea in Chapter 5 of his book Behavior: The Control of Perception:

The “reference signal” is a neural current having some magnitude. It is assumed to be generated elsewhere in the nervous system. It is a reference signal not because of anything special about it, but because it enters a “comparator” that also receives the perceptual signal. …

The comparator is a subtractor. The perceptual signal enters in the inhibitory sense (minus sign), and the reference signal enters in the excitatory sense (positive sign). The resulting “error signal” has a magnitude proportional to the algebraic sum of these two neural currents — which means that when perceptual and reference signals are equal, the error signal will be zero. If both signs are reversed at the inputs of the comparator, the result will be the same. The reader may wish to remind himself here of how a neural-current subtractor works by designing a comparator that will generate one output signal for positive errors, and another for negative errors. (This is necessary because neural currents cannot change sign.)

This reminds me of a chapter from book The Hacker’s Diet by John Walker

https://www.fourmilab.ch/hackdiet/e4/

It’s free online. He uses the thermostat analogy to describe some people’s ability to intuitively eat the right amount while others tend to over or under eat.

LikeLike

Interesting idea. But I don’t think “the body” gives a tin nickel for how fat it is, so all this talk of lipostats is geting the research heading down the wrong path. Furthermore, obesity is a symptom, not the underlying cause of poor health.

I believe that what “the body” cares about is two-fold: maintaining certain minimum levels of multiple nutritional inputs (i.e. salt, zinc, Vitamin C, water, etc) via feedback data from itself (the various organs/muscles/etc) AND interpreting the signals sent from the gut microbiome, which has a completely different modus operandi (and nutritional needs) to accurately regulate appetite.

In other words, an obese person with a deficit of Nutrient X is going to struggle to lose weight because there will continue to be strong signals to keep eating food until Nutrient X is successfully acquired.

Likewise, an unhealthy or weakened gut microbiome is not going to be able to send enough (accurate) data for “the body” to be able to interpret. As such, a lack of clear signaling will always result in “eat more food” even if there is no technical deficiency of a necessary nutrient because “eat more food” is the failsafe plan for this kind of emergency.

In a successful scenario, the two systems work together. The gut microbiome is thriving and eating well and sending full-bandwidth accurate signals to regulate appetite while “the body” also gets self-feedback that all is okay thanks to a balanced diet rich with all the needed nutrients. And in THAT scenario, obesity (caused by an imbalance of food intake/unhealthy gut biome) is non-existant, and the person is both healthy AND at a healthy weight (which varies by individual and environment and certainly has nothing to do with fucking BMI).

LikeLike

I think SMTM also agree that obesity is a symptom. But why wouldn’t some bodily mechanism that monitors “amount of body fat” be part of the causal chain? The body has ways to direct food energy in different ways, whether to store as fat or otherwise, and also ways to modulate appetite. These are probably connected on some level; might as well call that the lipostat.

Something going wrong with gut flora could easily be part of what’s breaking the lipostat. What is an observation or experiment that could distinguish that from the nutrients-stat mechanism you’re describing?

LikeLike

In control systems, “heads” are usually called loops. The most basic loop is a “P” (proportional) loop: the output solely depends on the current instant magnitude of the process value. A pure “P” loop can be made very accurate by making it very slow, or can be made very fast by making it very inaccurate. This is roughly comparable to how basic thermostats operate.

A “P”roportional loop will often be tightened by adding “I”ntegral and “D”erivative calculations (like in calculus 101!), giving you a “PID” loop. The controller will then account for recent PV variations over time, such that acceleration/deceleration (hysteresis and other time-based factors) can be accounted for.

Incorrect tuning of P, I or D values can completely break your loop, making it incapable of ever reaching the desired setpoint in some cases, or sending the loop into a permanent overshoot-then-undershoot state in other cases.

See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proportional%E2%80%93integral%E2%80%93derivative_controller

Perhaps also: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qKy98Cbcltw

A PID loop is certainly not the only type of control loop available—it won’t magically map 1:1 to biological systems as though PID is a direct expression of the will of the universe—but it is the single most common and best understood type of control loop because it’s simple and produces good results.

Recent PID controllers will also tend to offer an “autotune” feature where the controller outputs quasi-random values for some time, seeing how the process is affected. This is used to automatically figure out correct-ish P, I and D factors without human intervention. If a system is too complex or has unintended inconsistencies, then the autotune will generally fail, but it can also “succeed” and produce PID factors that will break your loop.

LikeLike

Thanks! We are a little familiar with PID controllers — if we understand correctly, P / PID controllers are what we called “target” control systems in this essay (this may not be the best terminology), in that they drive a measure towards a single reference value and are able to drive the signal both up and down (assuming the output function allows for that).

The distinction we’re trying to make here is that you can also have a controller that drives a measure to a threshold rather than a reference, and can only control movement in one direction (e.g. if it keeps a measure above a threshold, it only needs the ability to push the signal up), what we called “single-headed”. We’re not totally sure if this is a meaningful distinction, but it seems like it might be. What do you think?

LikeLike

What you call “single-headed” and “double-headed” are examples of “bang-bang” control”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bang%E2%80%93bang_control

LikeLike

Brilliant, thank you!

LikeLike

I was involved with some research 10 years ago in electronically herding cows. One thing I heard at that time was that farmers have perfected increasing the weight of their cattle, they know exactly how to do it. There is a fair amount of research published on this (some on PubMed I believe). A theory is that what makes cattle obese might also make people obese. Antibiotics increase the weight of cattle. Perhaps antibiotic-like things are added to human food, though they may be more herb-like mild antibiotics than like FDA approved drugs. Cattle are “finished” on grain to bring up their weight for the market. I think there are other methods as well, breeding certainly is another. Could be worth a look. Could be an example of something that changes the set points/reference levels for cattle, which might suggest things that change the set points/reference levels for humans.

LikeLike

Thanks! We did look at the case for livestock antibiotics causing obesity (https://slimemoldtimemold.com/2021/07/20/a-chemical-hunger-part-v-livestock-antibiotics) and found it plausible. Not currently our primary hypothesis but still some weight behind it!

LikeLike