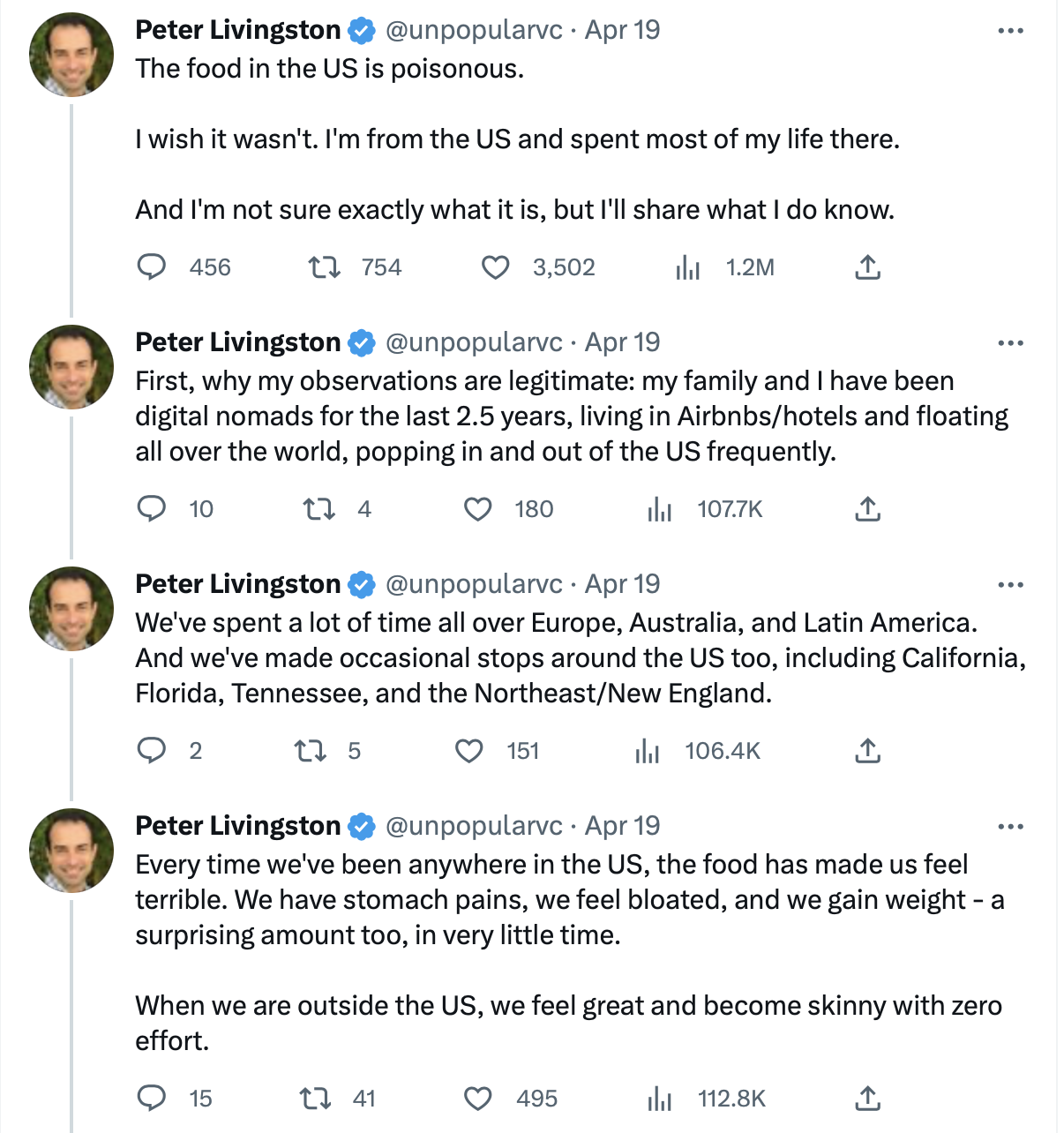

There are lots of stories where an American goes on vacation for a few weeks, to Europe or Asia or wherever, and loses a significant amount of weight without any special effort.

(Though sometimes it’s not weight, it’s something else like acne breakouts or digestive issues.)

There are also some stories that are exactly the opposite: someone from Europe or Asia or wherever goes on vacation to America for a few weeks, and GAINS a significant amount of weight without any changes.

Some stories describe what are almost simple ABABA-style experiments, where a person goes back and forth from America to other parts of the world and sees their weight reliably yo-yo as they move from country to country. We shared one such story in Part X of A Chemical Hunger, this account from Julius:

I currently live in Seattle but have moved around a lot. I’ve made 6 separate moves between places where I drank the tap water (mostly USA/UK/Hungary) and places I haven’t (South East Asia, India, Middle East). Whenever I’ve spent significant time in bottled water countries I lost weight (up to 50 lbs), and each time, save one 3 month stretch in Western Europe, I gained it back in tap water countries. I also lost weight for the first time in the States (20 lbs) this year around the time I switched to filtered water.

We can also share this story, from another reader (lightly edited per his request):

I quit my job and moved to northwest Thailand. I lived there for about 1.5 years and lost 100lbs. At the end, I was thinner than I’d ever been as an adult, even in Germany, just under 200lbs (or ~90kg). I didn’t do much if any exercise and I typically ate as much as I wanted.

Then I moved to SF and gained the 100lbs back within 2-3 years. I worked out while I was still thin, but, again, it didn’t stop the gaining and eventually became impractical as I was too fat to run. Peaked around 300lbs once again.

So then I thought, it’s the work stress. So I quit my job once more, and I moved to Las Vegas, where I lived for an ENTIRE YEAR without a job. And didn’t lose any weight.

During these last few years, I would often vacation in Thailand for 1-3 months, and always lose weight without trying. Typically, if I was there for at least 1 month, I’d see some noticeable fat loss on the order of a few pounds, and feel my belt get looser.

Even right now, as I’m visiting with my family back in Germany, I am visibly and belt-feel thinner after only 3 weeks of being outside the US, despite zero exercise and eating a ton of salami and cheeses.

Anecdotes are fun, but so far there hasn’t been any systematic study. If this vacation weight loss effect is real, it seems like it would be good to know. It would give us a powerful tool for causing weight loss (just take a trip to somewhere leaner than where you’re living right now), and it would help us get closer to finding out what causes obesity.

In particular, it would provide more evidence for the contamination hypothesis, since losing weight on vacation is a pretty strong hint that something about the environment is to blame. Most of the anecdotes above seem pretty confident their weight loss has something to do with the “unprocessed” foreign food, but there are reasons to think it might be some other part of the foreign environment. And if we could study vacation weight loss in a systematic way, we might be able to narrow things down.

Systematic

Happily, the plural of anecdote IS data, so these anecdotes do start us off with data we can use.

But this data is not very systematic, and may not be representative. In particular, if you go on vacation to Europe and you lose no weight, you probably don’t post about it on social media, and you probably don’t email us to tell us about the weight you didn’t lose.

We can correct for this by trying to collect data in a more systematic way. We can also try to come up with a design that lets us account for some alternative explanations (more on this in a bit).

We have a few ideas for study designs, but we’re not sure what kind of design would be best. We’ll describe general ideas for designs below, and please, let us know what you think.

If any of the designs seem good, we might run one of these studies at some point. But it’s somewhat of a shame for us to be running so many of these internet studies. No one should have to take our word for these things — it would be better if the work/knowledge/expertise were spread around the community.

So if you want to help run one of these studies, or if you want to take point and run it yourself, let us know and we can talk about collaborating. Or you can just take the design and run with it, we’re not your mom.

Walking

But first: Some people are skeptical that there is something special about vacation. The most common alternative they offer is some form of, “it’s all the extra walking”.

But there are some problems with this response. For starters, it assumes that all these people are walking more, but you don’t always walk more on vacation than you do at home. Some people have very active day jobs, and there’s nothing stopping you from sitting quietly in your hotel room for a week straight.

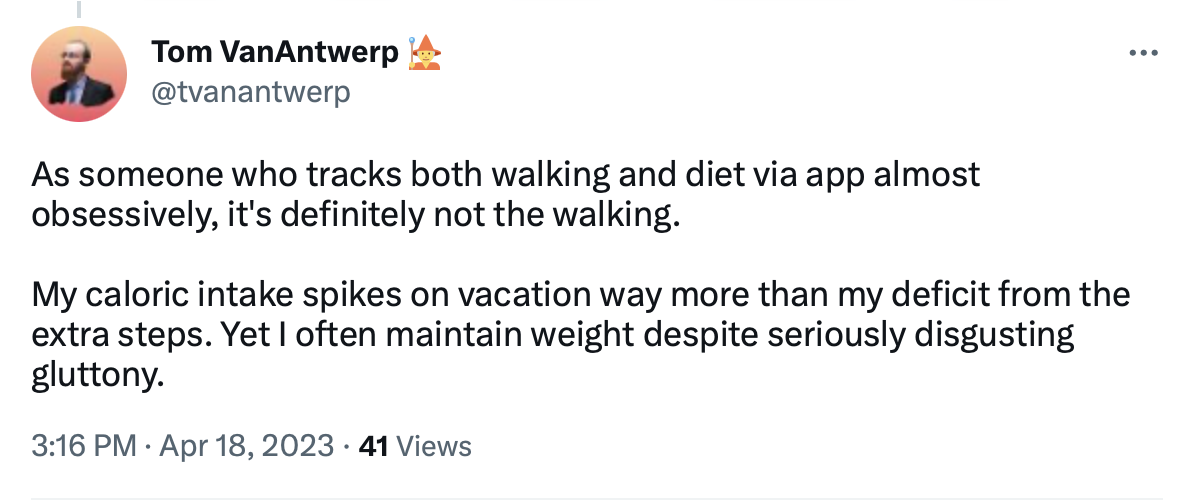

It ignores the other details people often mention in these stories, like that they also ate much more and ate “worse” than normal on vacation. From a simplistic CICO perspective, this extra food should balance out the extra walking.

And if extra walking on vacation were the cause of vacation weight loss, then extra walking ANYWHERE should cause weight loss. This would mean that slightly more mild cardio is a good treatment for obesity in general. But “slightly more mild cardio” doesn’t work as a treatment for obesity, so it’s clearly not the cause of vacation weight loss.

More importantly, many people who lost (or gained) weight on vacation make it clear that they don’t think it was the extra walking. Yes, they are not totally neutral parties, but no one is a totally neutral party, and they are the only ones with firsthand knowledge of their own cases.

There may be other reasons to doubt that extra walking is to blame. Friend-of-the-blog dynomight is skeptical that the walking explanation survives back-of-the-napkin math:

But all this debate is really for nothing. We can just check.

For starters, it’s easy enough to ask people to count steps. Their phones make estimates automatically. We can see if people are walking more on vacation and if how much extra walking they do is at all related to how much weight they lose.

We can compare Americans who go on vacation to Europe with Europeans who go to vacation in America. Maybe both groups walk more than average while they’re on vacation, but if the Americans lose weight in Europe and the Europeans gain weight in America, that would suggest that the extra walking has little to do with the weight change.

We can also compare between states. Different US states vary widely in their obesity rates, from 25% in Colorado to more than 40% in Kentucky. If it’s something about the environment, then people from Kentucky should lose weight when they vacation in Spain, but people from Colorado might not. Similarly, we can look at people taking vacations in different US states. Europeans might gain weight in Mississippi but might not gain weight in Massachusetts.

We could even do something ludicrous like: “take identical obese twins, send one twin on vacation to Italy and have the other twin stay in America and try to match their walking distance as closely as possible.”

With the right design, it should be relatively easy to tell if walking is to blame. It’s fine if somehow it turns out that extra walking is the real cause of vacation weight loss, but clearly this is somewhat controversial — we should do a study and see.

Design #1: Existing Cohort Study

First, we could use data that someone else has already collected.

Programs like the Fulbright Program and the Peace Corps send young people to different countries around the world. These programs are already doing a controlled study on the vacation weight change effect, they just don’t know it. For example, the Philippine-American Fulbright Commission takes young people from a fat country (America) and sends them to a lean country (the Philippines), and also takes young people from a lean country (the Philippines) and sends them to a fat country (America), in both cases for about a full year.

These programs may already be recording students’ weights before and after their trip abroad, perhaps for medical reasons. If so, all the data we need already exists out there in some database. If not, all that would be required would be convincing the program, or even just some of the students, to start recording their weights before and after the exchange.

This is pretty much the ideal experiment. It’s systematic — we will get information from everyone, whether or not they gain or lose weight. The sample size is huge. And the data may already exist.

The problem is that we don’t know if there’s any way for us to GET this data. We haven’t had any luck trying to get in touch with Fulbright or any of these other programs, and we doubt they would be willing to make this data public.

If anyone thinks they could put us in touch with anyone on the Fulbright Philippines Board of Directors, or anyone at a similar organization (the American armed forces might have similar data), we would love to do this analysis. But barring that, we’ll have to come up with ways to collect our own data.

Design #2: Retrospective Vacation Study

Second, we could collect vacation information that already exists.

People have gone on many vacations over the course of human history [citation needed]. So for this design, we would systematically collect all the existing vacation stories we can.

This could be as simple as setting up a google form and asking people to submit stories about their past vacations (or other international trips, like exchange programs or briefly being an expat). The form would include just a few simple questions — how long the trip was, how much they weighed before, how much they weighed after, where they went, etc. Then we could look at this data to see if there’s any support for the vacation effect.

You might want to limit this (and the designs we talk about below) to trips that are at least two weeks long, because one week probably wouldn’t be enough to get a clear signal.

The upside of this design is that you might be able to get a lot of data pretty quickly. But there are some downsides.

First off, people may not remember how much they lost, how long they were gone, or other details of the trip. In short, the measurements will be noisy.

Second, you can’t ask people to collect specific data, or ask them to collect it in specific ways, because the vacation has already happened. If people happen to have measurements of how much they walked on their vacation, that would be great, but most people won’t have collected that data.

Finally, there’s bound to be a selection effect. People who lost weight on vacation are probably more likely to respond than people who gained weight. This isn’t totally damning since we can still see things like 1) whether people lost more weight on longer vacations, 2) whether people lost more weight when they traveled to leaner countries, or 3) whether younger people lost more weight than older people. But it is a limitation.

So it would be easy to run this study, and maybe informative if we got enough responses, but there are some problems with this kind of design.

Design #3: Prospective Vacation Study

Third, we could collect vacation data as it’s being created.

People continue to go on vacations today; in fact, many people are planning vacations right now. So another option would be to ask people to sign up to report on any vacations they’re about to take, and provide us a little data about the before and after.

The design would be pretty simple: first a pre-vacation survey, where people tell us about the vacation they’re about to go on, where they’re coming from, where they’re going, how long it will be, and how much they weigh right now. We’d also ask them to give us some measure of their average activity, maybe their average steps per day over the last three months — something easy that should already be captured by their phone.

Then when they get back, there’d be a post-vacation survey, where people could tell us what their weight was after the vacation. We’d also ask them for their average steps per day while on vacation, so we could get a sense of if they are walking more or less than normal. We could also ask them to report subjectively on measures like whether they exercised more or less than usual, and whether they ate more or less than usual.

This would help keep selection effects somewhat in check. No one knows before a vacation whether they will gain or lose weight — they can’t decide whether or not to sign up for the study based on their weight change, because it hasn’t happened yet.

If we have a high attrition rate, with lots of people filling out the first part but not filling out the second, this could be a sign that people who gain weight don’t come back and report their weight gain. But if the attrition rate is low, that suggests there isn’t much post-hoc selection.

We can also do comparisons just within the people who respond. Maybe the attrition rate is high, but if all the Americans going to Europe report losing weight, and all the Europeans coming to America report gaining weight, we can be fairly sure that’s not just selection.

The downside is that this approach would be pretty slow. There are lots of vacations, but we have to wait for people to come to us one by one as they jet off on their various trips.

This design is also not very controlled. We don’t get to pick the vacations and we don’t get to pick the vacationers. It’s a convenience sample, and while it might still be revealing, there are limitations.

Design #4: Controlled Vacation Experiment

Fourth, we can go out of our way to create the data we want.

It’s within our power to make vacations happen under controlled conditions — recruit some people who are obese and who can spend a month or two abroad (perhaps they have a remote job), and send them to a lean country for a couple weeks to see what happens. As with the other designs, you could have them track their exercise and other confounders if you want.

This is a version of what we have previously called “Slime Mold Time Mold’s Excellent Adventure”.

We were originally concerned that even if things were perfect, weight loss would be pretty slow. Even if you sent people to Japan for a month, they might not lose weight quickly enough for you to reliably detect the change. We thought that you might have to send people abroad for closer to a year, just to pick up on the effect.

But the results of the Potato Diet have convinced us that under the right conditions, quite a lot of weight loss can happen in just a few weeks. So now we think that a vacation study of 2-4 weeks might actually be informative.

And you may not need very many people. It’s still not clear how many people lose weight on vacations, but if the effect is consistent enough, you could find strong evidence with just a few participants (yet another n of small opportunity). If five obese people go to Italy for a month and all of them drop 10 lbs while sitting around and eating spaghetti alla carbonara ad libitum, that would be strong evidence, even with the small sample size.

The ideal countries to send people to would probably be Vietnam (leanest country in the world, about 2% obese), Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Japan, or South Korea (all less than 5% obese). There are many relatively lean countries in South America and Europe, but even Albania is more than 20% obese, so you would probably get a weaker effect.

This wouldn’t be too expensive. It costs around $4,000-$5,000 to send someone to a lean country for a month, so you could likely send around 10 people to one of these countries for a month for less than $50,000. Not pocket change, true, but cheap in the grand scheme of scientific studies. Given that many people enjoy vacations [citation needed], you might even be able to get people to pay for half of their trip.

It might make sense to run one of the other studies first to see if they back up the anecdotes, before spending all this money. But the other study designs aren’t nearly as controlled. If you’d be interested in funding this study, or helping us arrange all the travel details (booking hotels and flights is not our strong suit), please let us know. Or you can ignore us, recruit 10 obese volunteers, and send them to Myanmar all on your own. Just let us know what you find out!

Similarly, anyone who is at all overweight could run this as an N=1 self-experiment, or get a few friends and run it as an N of small. You just need to be in a position to spend a few weeks in one of these lean regions.

The main drawback is that the small sample size would keep you from making interesting comparisons. Sending 10 obese Americans on a one-month trip to a small Asian country could make a strong case for the vacation effect, but it wouldn’t let us answer questions like the following: do young people lose weight faster on vacations than old people? Do other demographics (like ethnicity) have an impact? Do people lose weight faster in Peru (19% obese) than in Spain (27% obese)? Do people with BMI < 25 also lose weight on vacations?

This would be another reason to run multiple studies with different designs. Sending people on a planned vacation gives you a lot of experimental control with the limitation of a small sample size, while other designs can give you a large sample size at the cost of experimental control. Both could tell us a lot, and they’d be stronger together — triangulation is the name of the game.

Final Notes

As far as we know, no one has ever done a vacation study like this, so any study at all would be interesting. It doesn’t have to be perfect — we should start by getting our toes wet.

We’re talking about these designs like they’re all about obesity, but this approach doesn’t have to be used to study obesity. You could also use it to study, say, migraines. Lots of people think they are gluten or lactose intolerant — but are they still gluten or lactose intolerant if they’re eating bread or milk in, say, Italy? Might be interesting to find out.

As always, we are happy to help with designs and methodology. If you want to run one of the studies described above, please contact us!