I.

Cholera gives you severe diarrhea, which leads to agonizing, life-threatening dehydration.

Doctors long realized that cholera patients needed electrolytes, but electrolyte solutions didn’t seem to help. In fact, giving patients electrolytes in IV or in an oral solution often made them worse.

After decades of trial and error, they discovered a mixture of water, electrolytes, and sugar that would treat the dehydration from cholera instead of making it worse. This brine came to be known as oral rehydration solution (ORS), and is now the standard treatment for extreme dehydration.

One thing that might surprise you about this mix is that sugar is an active ingredient. It’s not just for taste — the brine literally doesn’t work without it. As it turns out, for esoteric biology reasons sodium can only be absorbed in the gut when it’s paired with glucose:

Why did [early attempts] at oral rehydration fail? It seems that the scientist[s] didn’t yet know some of the fundamental biology of how glucose and sodium was absorbed in the body. Work in the late 1950s and early 1960s had established that sugar and sodium ions are absorbed together in the gut through a sodium-glucose cotransport protein. In turn, this sodium and glucose pulls water from the gut into the body.

Another surprise is that you need to get the solution just right. You can’t just pick a random point in brinespace. As researcher Robert Allan Phillips discovered, if you choose the wrong ratio of ingredients, you kill your patients instead:

The trial was a disaster. When Phillips returned to Manila a week later he was told that five of his 30 trial participants had died. It’s not clear exactly what went wrong with Phillips’ experiment, but we do know that the oral solution he put together had far too much glucose and salt. This made the solution extremely hypertonic — it drew water out of the patients’ cells and exacerbated their dehydration.

Functional solutions for cholera exist only in a relatively small range. Go too far outside that range, and the solution hurts your patients instead of helping them.

We don’t know how narrow that range really is. But we do know you have to get the mix right, or it doesn’t work.

II.

Any combination of electrolytes in solution can be expressed as a point in high-dimensional brinespace.

We begin with a liter of water, the origin along all dimensions. A simple brinespace might define a brine by the concentrations of sodium and potassium per liter, written as [mg Na, mg K].

The point [100, 100] would indicate a brine that contains 100 mg each of sodium and potassium per liter of water. Official concoctions of ORS are more complex, but the simplest make-it-at home version of ORS is located at the point [1150, 0].

But that’s not quite right, is it? ORS contains other ingredients than just sodium and water. Most notable is sugar. If we define a new brinespace of [mg Na, mg K, g sugars], then ORS is located at [1150, 0, 25].

Gatorade is another simple brine. With 270 mg sodium, 80 mg potassium, and 34 g of sugar in a 20 oz bottle, it can easily be defined as the brine at [460, 135, 60] (with some rounding).

One “stick” of the electrolyte mix LMNT contains 1000 mg sodium, 200 mg potassium, and 60 mg magnesium. We’ll have to add magnesium to our brinespace, which we’ll now define as [mg Na, mg K, mg Mg, g sugars]. They recommend you mix this with “anywhere from 16 to 32oz of water”. Given that 32 oz is approximately a liter, this means that LMNT produces brines approximately along the line from [2000, 400, 120, 0] to [1000, 200, 60, 0].

Other electrolyte drinks can be characterized the same way. LiquidIV is located at [1060, 780, 0, 25]. Pedialyte is almost the same (at least in terms of these dimensions), resting near [1030, 780, 0, 25]. Propel (a Gatorade product), has no sugar and can be found at the coordinates [460, 120, 0, 0].

Even Red Bull is something of a brine. If we define a new brinespace that includes caffeine [mg Na, mg K, mg Mg, g sugars, mg caffeine], then Red Bull is located at approximately [420, 0, 0, 110, 320].

Red Bull isn’t even that unique for having caffeine. Thirst Quencher 2 (TQ2), the forbidden sequel to Gatorade, itself contains caffeine. While Quaker Oats sued to take ownership of TQ2, and then buried it forever such that it has never seen commercial release, we have what appears to be the patent, which defines TQ2 pretty well. Ignoring the phosphate, glycerol, and pyruvate for the moment, we can use the same brinespace as Red Bull. In terms of this brinespace, TQ2 appears to be at about [600, 80, 0, 40, 150], compared to standard Gatorade at [460, 135, 0, 60, 0].

TQ2 makes it pretty clear that the only sugar it contains is glucose, while in standard Gatorade the sugar is some combination of sucrose (50% glucose and 50% fructose) and dextrose. In case that makes a difference, and assuming for the moment that standard Gatorade contains only sucrose, we might want to define a new brinespace [mg Na, mg K, mg Mg, g glucose, g fructose, mg caffeine], in which case TQ2 is located around [600, 80, 0, 40, 0, 150], with standard Gatorade at [460, 135, 0, 30, 30, 0].

(This makes us wonder if glucose is functionally different than other sugars. ORS recipes specify glucose, which suggests that other sugars might not work. TQ2 claims to be an improvement on Gatorade and also specifies glucose. Does fructose not fill the same functions? Is there no sodium-fructose cotransport protein?)

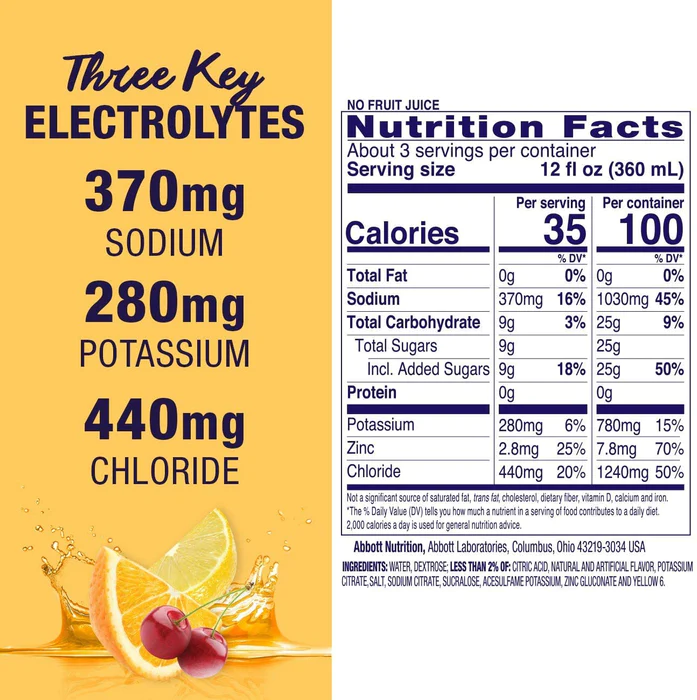

The astute reader will have noticed that all the ions we’ve been talking about up to this point are cations. What’s up with that? Is there some kind of big prejudice against anions? Of all the mixes we’ve looked at so far, Pedialyte is the only one that lists chloride on its nutrition facts label, though most electrolyte solutions presumably have some chloride, since most use NaCl or KCl. Pedialyte in fact gives a percent daily value of chloride (440 mg is apparently 20% DV). We had no idea chloride even had a recommended daily value. But it is in fact an essential electrolyte — without it, you die.

Or how about iodine? That’s an essential electrolyte, it’s a anion (as iodide), but it’s never added to electrolyte drinks, never mentioned on nutrition labels. Maybe people don’t want to hear about chloride ions in their Gatorade, because it makes Gatorade sound like it’s chlorinated (which in some sense, it is), but why not iodide? Any electrolyte mix that includes iodized salt will contain both iodide and chloride, and both of them are biologically active.

A brine might contain any number of other ingredients, and these don’t necessarily need to be electrolytes or sugars.

For example, you could define a brinespace that includes some acids. Ascorbic acid (AKA vitamin C) would be one natural choice — in this case, your brine would cure scurvy. You could also include citric acid. This is certainly found in lemonade, though it’s not clear whether it’s an active ingredient in that context.

Or how about acetic acid, better known as vinegar? The health benefits are controversial, but there are many cultural drinks that are basically just sugar + acetic acid. The ancient Greeks had oxymel, the Romans had posca. Persians have sekanjabin, England gave us “shrubs“, and New England has switchel. Lots of cultures seemed to settle on this combination independently, and kept with it for hundreds of years. Maybe there’s something to it.

Even Milk is a brine. It contains sodium and potassium, calcium, sugars, even iron. It’s an unusually complex brine, sure, but a brine nonetheless.

III.

Some brines have health and wellness benefits.

ORS is the clearest example. Brines from the correct region of brinespace provide a fast and effective treatment for the intense dehydration of cholera. Go too far outside of that region of brinespace, and the brines stop working, then start making the patients worse — some brines will even kill them. It doesn’t work if the ratios are off! Finding the correct location in brinespace matters a lot.

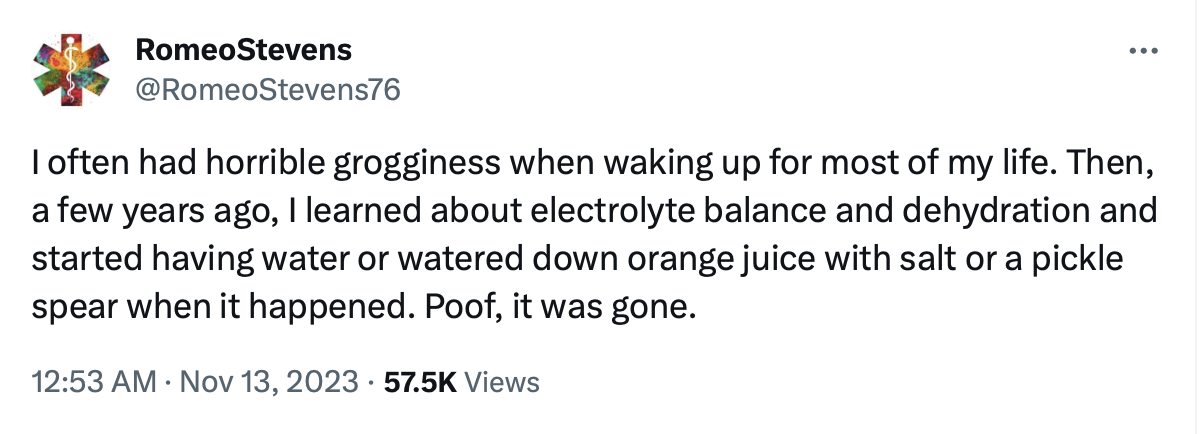

While ORS is exceptional, we don’t think it’s unique. For starters, we have anecdotes like this one:

The extreme version of “grogginess on waking” is hangovers. If you take Pedialyte for hangovers, you are already brining. The company also believes in this application — they recently released a formulation for just that situation.

Sports drinks are another obvious example. Gatorade makes $7 billion in sales per year. Either Gatorade provides some kind of benefit, or their marketing team deserves a raise.

And there are the direct testimonials. Robb Wolf, the co-founder of LMNT, says:

Salt-deprived rats are sad. They loaf around their cages, ignoring the sugar water that usually brings them joy. It’s classic depressed behavior.

I unwittingly ran a similar experiment on myself for the better part of 20 years. I was sweating buckets—unlike pigs, who don’t actually sweat by the way—on the jiu-jitsu mat, but wasn’t consuming enough sodium to replace my losses. I felt low-energy, foggy, and, as I think back, losing passion for my sport. I wasn’t giving my body what it needed, and my mood paid the price. Getting more salt was the remedy.

Compared to other factors, the link between sodium status and mood isn’t well-publicized. I want to change that. I’m not saying salt is a cure for depression, but I do believe it’s worth considering as part of a holistic approach to mood maintenance. Mental health is the fruit of many inputs. And oftentimes many things are out of our control, but getting enough sodium isn’t one of them.

If Robb is right, then some cases of “depression” might just be a chronic lack of electrolytes. This would be simple to test.

Like ORS, Robb also claims that the wrong mix of electrolytes doesn’t work. In our terms, you need to find the correct point, or at least the correct region, in brinespace.

POPULAR PRODUCTS DIDN’T CUT IT. … When I dialed in the formulation I immediately felt my fitness, sleep, and brain functioning on new levels.

Sodium and glucose aren’t the only ingredients where you need to get the mix right. One of our friends, a physician, pointed out that for patients with low potassium (hypoK), if you don’t have enough magnesium (hypoMg), you’ll be hypoK forever unless you fix the hypoMg first, because of “some renal excretion thing I think” (his words). See also this paper, which says: “magnesium replacement is often necessary before hypokalemia and potassium depletion can be satisfactorily corrected with potassium supplements.”

Of course, most regions of any brinespace are going to be unremarkable, or slightly dehydrating. But there are reasons to suspect that some brines, in some situations, are the perfect solution.

IV.

Here are three candidates for new brines with plausible health benefits:

First, we think there’s evidence that high-potassium brines can cause weight loss.

Ketoade is a term for various concoctions of electrolyte drink, usually high in potassium, that people often drink while on ketogenic diets. People mostly seem to drink this to fight “keto flu”, which may just be the feeling of not having enough electrolytes. But ketoade might also be part of the reason that people lose weight on keto diets. Not from the diet — from the extra potassium.

When we ran the potassium trial, people took supplemental potassium, usually in water or as part of a concoction. On average, people lost weight, a mean of 0.89 lbs over 29 days (n = 104, p = .014).

Despite being statistically different from zero, 0.89 lbs obviously isn’t much in practical terms. But people who took more potassium lost more weight on average (r = -0.276, p = .005), which is additional evidence that there’s something here. And three people lost more than 10 lbs, suggesting that there might be specific ways of taking potassium that are especially effective.

These three participants seem to be more than outliers. For example, here’s one of their reports:

(77174810) First of all – holy shit! It’s amazing how well this worked and it’s also surprising that it’s never really been studied before! Thank you for the analysis and thought that you put into this. For this trial, I basically just ate whatever I felt like, went to a football tailgate party nearly every weekend with lots of beer and foods you would not associate with dieting… and still lost nearly 10 lbs!

…

I have tried every diet/exercise and variation of CICO, atkins, keto, IF, etc., etc., etc. to try and lose weight. To no one’s surprise, nothing really worked for long and the weight always came back. At the end of 2020 I was over 275. It took me three months of busting my ass to lose 20 pounds and as soon as I started eating “normally” again, I slowly started putting weight back on.

Of interest to our point today, this participant took his potassium in solution. If there is an ideal brine for losing weight, it might look something like this:

(77174810) What I discovered was that mixing [potassium] with Simply Strawberry Lemonade makes it very palatable! I dissolved the KCl and a little sea-salt in about 1 oz of water. Then added about 4-6 oz strawberry lemonade. You could damn near sip it this way! Apple cider was the second best mixer.

But the strongest evidence that high-potassium brines can cause weight loss is certainly Krinn.

After some success as a participant in the potassium trial (6 lbs lost), Krinn decided to keep going, increasing her potassium intake and searching for a protocol that she could stick to long-term. At the six month mark, she wrote a tumblr post as a report about her progress. You can read her report here and our review of that report here. Here’s how she describes her approach:

I decided to stabilize at about 10,000mg [potassium] per day … because that’s about how much potassium people were getting during the SMTM potato diet community trial. … Aiming for that amount also meant that it would be easier to compare my results to something that worked decently well and to ask questions like ‘is there something special about whole potatoes, or is it mostly the potassium?’ If it’s mostly the potassium, you’d expect my results to be closer to the full-potato-diet results than to the low-dose-potassium results — which is what happened.

We can also offer a brief update on Krinn’s progress after just over one year (shared with her permission). Take a look at the plot below. As you can see, her weight loss continued until she hit a plateau at just above her target weight, which corresponds to a BMI of 25. She tells us that she’s not sure if this is because the potassium stopped working, or if it’s as a result of external life situation reasons.

Krinn took her potassium as a brine. Specifically, she mixed potassium chloride with Gatorade. Here are the details:

I used potassium chloride powder (whatever came up first on an Amazon search since all KCl should be alike) mixed with regular Gatorade (i.e. not the sugar-free kind) to make it taste okay (I recommend blue Gatorade, it’s the closest to appealing when kaliated — the yellow lemon-lime was meh and the fruit punch red was awful). I added two heaping teaspoons of KCl powder to a 20oz. bottle of Gatorade and drank that. KCl is about 52% potassium and a heaping teaspoon of it is about 6500mg, so I rounded up a smidge and called that 6600-and-a-bit milligrams of potassium per bottle. On Thursdays and Sundays I have drank 2 full bottles and on other days 1.5 bottles. I recorded this as 10,000mg of potassium on regular days and 13,500mg on Thursdays and Sundays.

Comparing Krinn to the participant we mentioned above, who mixed their potassium chloride with strawberry lemonade, we notice a few things in common.

Both of their potassium solutions contained sodium — Krinn from the Gatorade, while the other guy added sea salt. Both of them included sugar, from the Gatorade or the strawberry lemonade. Given what we know about ORS, it seems reasonably plausible that sugar might have an important interaction with potassium. And curiously, both included citric acid, since both Gatorade and strawberry lemonade contain some citric acid.

The biggest difference is the potassium dose — Krinn was getting about 10,000 mg a day from her brine, while the other participant was getting only 3,000 mg/day or so. If there is an ideal weight-loss brine, it probably exists somewhere in the neighborhood of these two approaches.

(That said, it’s not clear that such high doses of potassium are safe for everyone, and they almost certainly are not safe if you have kidney disease or related diseases like diabetes. Do not try supplementing doses this high without consulting your physician, and absolutely do not try it if you have kidney problems or any conditions that might compromise your kidney function.)

In our review of Krinn’s post, we also noted two things. First, Krinn was getting lots of magnesium on the side, through the rest of her diet. And second, she seems to eat a diet high in stearic acid. These are both ingredients that have attracted some suspicion for possibly being related to obesity, which caught our attention. You could plausibly add magnesium to your brine without any trouble (and some brines like LMNT already include a small amount of magnesium). But stearic acid is a butter-like waxy solid, it would probably not go well in most brines, though it is found in milk. Is dairy a weight-loss brine? Well, ExFatLoss would probably say yes..

Our second brine candidate is that we suspect there might be a brine or brines for IBS.

ORS was made to treat the dehydration associated with diarrhea, not the diarrhea itself, but even so it was designed to specially calibrate your digestion. “I’ve had IBS-D,” writes u/feelslikehel, “for about 8 years. I’ve been doing the salt and water regimen for about 6 weeks now and it’s not really making me feel less dizzy but I’m finding that my IBS-D is pretty much gone.” If you have IBS with diarrhea, it might be worth mixing up some ORS. If nothing else, it will help keep you hydrated. Also compare: Large increases in sodium intake are recommended for POTS.

Or how about “Hot girls have IBS”? Hot girls tend to have something else in common — we pay a lot of attention to what we put in our bodies. No processed food, nothing that might disrupt the microbiome. Have you been avoiding salt and sugar to help with your digestion? If so, remember that both sodium and glucose are necessary for your body to absorb water from your gut.

Finally, our third candidate is that there might be a magnesium brine for migraines.

There’s some evidence that oral magnesium supplements can make migraines less intense and less frequent (meta-analysis). This evidence could certainly be more consistent. But as we’ve previously seen, sometimes the right mix can be a big multiplier. Perhaps there is a magnesium brine that would be so much more consistent, or more effective.

But even assuming there does exist some brine that will treat your ailment, or will just help you feel less groggy in the morning, you still need to find it. Or to put it another way, you’d need to discover its location in a high-dimensional brinespace.

IV.

The space of all possible brines is very large. To find other brines with health benefits, we will need to develop new tools.

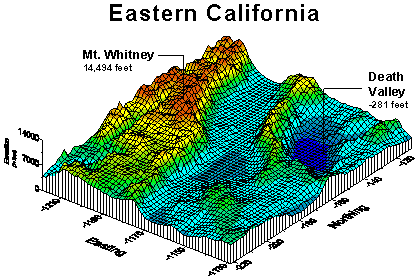

Behold! A 3-dimensional representation of a (hypothetical) high-dimensional brinespace, with height and color indicating “impact on migraines”. The red areas of brinespace are regions of brines that will make your migraines worse; the yellow areas will make no difference; and the blue areas are regions of brines that will make your migraines disappear.

If everyone’s brinespace is largely the same, then it will take only one courageous migrainenaut to map its murky bottoms. But as we know, people are not much the same. And neither are migraines — if there are two or more kinds of migraines, those brinespaces will have to be mapped separately. Perhaps your neighbor’s biology is very different from yours, or she has the other kind of migraine, and her migraine topography looks like this instead:

Who knows what these topologies would look like in real life, how deep their local and global minima might go, how much they might differ between people or over time. But that’s the point. We are going into this with a lot of uncertainty, so we should go into this with caution, and with the right tools.

Software for searching brinespace should be modular.

❀

The first module would be for the brine ontology, the way of defining the brinespace you want to explore.

Put simply, there are many ways to define a space of possible brines. Some are simple, like the space [mg Na, mg K]. Some are more complicated, like the space [mg Na, mg K, mg Mg, mg Ca, mg Fe, g sugars, mg caffeine].

Some brinespaces make distinctions that others do not. For example, the space [mg Na, mg K, g sugars] treats all sugars as alike, or you could say, treats them as indistinguishable. But [mg Na, mg K, g glucose, g fructose] distinguishes between two common sugars and excludes all others.

Brinespaces can also define their terms in different ways. We’ve been defining these spaces in terms of the mass or volume of the different ingredients (g, mg, L, etc.). But for the scientist mixing brines at home, it might be easier to define these spaces in teaspoons rather than grams, and ingredients like KCl or NaCl instead of the individual elements. This makes it easier to think in terms of making the brine, in terms of operations — how many teaspoons of each ingredient to add to each liter of water.

On the other hand, defining it this way can lead to ambiguous regions of brinespace, and some information may be lost. For example, a brinespace expressed in teaspoons of ingredient salts wouldn’t include the information that adding KCl and NaCl both increase Cl−. If chloride ion concentrations are important, this brinespace would obfuscate that information. With that information, it’s clear that you could add baking soda (NaHCO₃) to a brine to add sodium without any additional chloride ions, or add potassium citrate (K₃C₆H₅O₇) to a brine to add potassium without any additional chloride ions.

Finally, any brine ontology should include some kind of safety limits. A brine might reasonably contain 200 mg/L potassium, but 20,000 mg/L potassium would be dangerous. No need to explore those regions. Exactly where to set these limits is up to the architect, but they should set upper limits on all the dimensions, and set them carefully. Options should be included for special populations, like people with heart conditions, who need to avoid high levels of sodium. Lower limits are not needed — if the dimensions are all at zero, you are simply drinking water. Yum.

Perhaps over time we will find a single large brinespace that is ideal for all purposes. But we might also find that different brinespaces are better for characterizing some searches than others. It’s important that this element be modular, so different brine ontologies can be switched out and tested at ease.

❀

The second module would be the outcome measure. We imagine searching brinespace for mixes that improve health and wellness, and this is the module where we decide how to measure the elements of health and wellness we want to improve.

For example, if you were following Krinn’s example and trying to discover a brine that will help you lose weight, you will want a module that measures your weight loss. A simple measure would be “each brine is rated on how much weight you lose over the next day.” But weight loss can be very noisy, so this might be too sensitive. A better measure might be rating each brine on a weighted average of weight change over the next several days.

If you are looking for something else, you want a different measure. For example, if you have “a horrible grogginess when waking up for most of [your] life” like Romeo Stevens did, you might be looking for a waking-up brine, or a sleepytime brine, to make your mornings a little brighter. In this case you might want a simple measure like, “on a scale from 1-10, how good do you feel 10 minutes after drinking your morning brine?” Or you could do some kind of complicated measure where you test your visual acuity, strength, and reaction time. It’s all the same to us.

If you are trying to find a brine to help your migraines, you could take a simple measure like, “on a scale from 1-7, how bad were your migraines this week?” Or you might find a need for a better scale, like a weighted combination of how many migraines you have each day, and how bad each of them was. You might even include some information about specific symptoms or features.

The point is, there will be many different things that people might want to find a brine for — for weight loss, for their migraines, for after a workout, for general clarity and energy. And for each of these targets, there will be many ways to measure success and progress. Some will be simple, some will be complex, some will just be different. You will want your measures to be modular so people can slot them in and out freely, to reach their own goals as they see fit.

In addition, each module should probably include basic check questions like, “do you like this brine” and “is this brine at all palatable”, as another safety feature. If you find yourself exploring a point in brinespace that you find truly noxious, you should probably just toss that mix and rate it as a failure on all measures.

On the one hand, this approach would exclude potential brines that are disgusting, yet secretly good for you. On the other hand, we doubt that many such brines exist. If a brine is gross, it’s probably bad for you. Your body is in fact designed to deal with these things. And in reverse, if a brine mixture tastes great, that’s an early sign that it might be good for you.

(As a note, you should probably mix your brine with some kind of flavoring. If you drink your brine with water alone, you might accidentally condition yourself to expect that water is dehydrating, something we discovered in the course of our self-experiments.)

❀

Finally, the third module is for the search algorithm and its settings. This is the procedure the software will use for searching the brine ontology or brinespace (the first module you set), and looking for brines that are effective in terms of increasing or decreasing the outcome measure (the second module you set).

Despite the title of this post, the best kind of search algorithm for brinespace is probably simulated annealing. However, we would love to hear elaboration or correction from anyone with more experience in this area.

We shouldn’t assume that the topology of the brinespace will be static for any outcome. In plain language, we might be aiming at a moving target. The best brine today won’t always be the best brine tomorrow. You will be eating other things, exposed to the environment, and also aging. So the search algorithm should always include some amount of exploration, no matter how well it’s doing. It shouldn’t rest on its laurels.

❀

Assuming you define your outcome clearly enough, you choose the right kind of search algorithm, and you give the algorithm enough time, it should eventually find you the best possible brine for your outcome (as measured) within the brinespace you defined.

That’s quite a few assumptions, and assumptions that are easy to get wrong on the first try, or first few tries. If you have spent a lot of time searching with no success, you might want to try different brine ontology modules or different outcome measures, in various combinations. If the software is especially clever, it might be able to help you with this.

But a long search with no success might also mean that there’s no brine that will help with your problem. This is possible and in fact likely in many cases. There is no brine that can cure a broken heart — in fact, high levels of sodium are dangerous for those with heart conditions. But for some problems, the ideal brine or brines may yet be out there.

Special thanks to Krinn and Potassium Participant 77174810 for their pioneering work in the exploration of brinespace.

Nice one. A topic close to my (dehydrated, shrivelled) heart.

The way I read this post is you’d like to do some n=1 science here but you’ve realised the space is so big that collecting data is going to suck.

I wonder if a quick way for a person to explore the space might be to make a range of drinks. I’m seeing 25 small cups laid out on a tray in a 5×5 array.

Sodium in one dimension, potassium in another.

Perhaps another 5×5 array on another tray with a different glucose level. You could end up with a lot of trays here!

The quickest way for that person to test the brinespace might be to trust the ancient links from tongue to brain – whichever one your body wants to slam down fast is possibly the ratio that’s treating you best.

Idle thought: a way to collect a lot of data from many people might be to make this a TikTok trend. #25cupsforhydration. I can imagine all the diet influencers making funny faces as they taste the different cups and telling us which combo they like most…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, absolutely! We would love to try this, but also happy to hear from anyone who is able to try it first! Are any of you readers TikTok influencers?

LikeLike

What is happening when I consume salted water in a fast? Cleese the salt has a salutary effect which I can feel. How is this happening if it’s impossible for me to absorb it?

LikeLike

How long do you reckon it would take to explore the brine space to determine if there is a brine for your problem? 🤔

LikeLike

Very hard to say! Probably depends a lot on the problem. But they did find ORS basically by trial and error, which makes us optimistic. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

We will be like slimes,

branching across the brines.

LikeLike

I wonder if there’s a “literature review” to be done here where reviews for all of the commercial brines are scraped for keywords like “migraine” and “ibs” and “flavor” to establish some reference points.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would strongly recommend against simulated annealing as it would require a lot of function evaluations (which is the costly part here) and would instead recommend Bayesian Optimization. Your problem is very similar to hyperparameter optimization in ML, you could look into what people use there too.

LikeLike

Anyway, thank you for this. I realized that my desired morning breakfast might be because I wanted salt and orange juice. Will try this instead.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Morton Light Salt! 1/2 NaCl 1/2 KCl. So simple to increase the daily potassium. I’ve been harping on this stuff for years and all I get is crickets at best or some strange push-backs at the other end. OK, mixing brines is useful for a lot of scenarios but for general life it seems like there’s simpler ways to ensure adequate minerals.

LikeLike

Good stuff. And it is iodized.

LikeLike

this is so interesting. I’d tried to lose weight a handful of times before I started HRT and in my second year I finally found that things were starting to actually work, even thought it was really difficult to stick to a calorie count. I wonder if that had anything to do with the fact that I was taking a buttload of spironolactone which is known for causing high potassium as a side effect.

LikeLike

since we’re optimizing a function with known bounds on all dimensions and do not have gradients available, we’re going to want to look at algorithms in the “derivative-free optimization” space, particularly those that are tailored to low numbers of function evaluations (i.e. trials). A great choice is DIRECT, but since these trials are likely to involve significant uncertainty, a better choice might be EGO (efficient global optimization), which is a Bayesian method which works by fitting a “response surface” or “surrogate model” to your trials and then minimizing that. One nice benefit of this latter method is it works well with noisy data and gives you not only the value of the response surface at any given point but also an associated uncertainty.

Here’s a (very readable) paper explaining the method (PDF)

http://www.ressources-actuarielles.net/EXT/ISFA/1226.nsf/8d48b7680058e977c1256d65003ecbb5/f84f7ac703bf5862c12576d8002f5259/$FILE/Jones98.pdf

LikeLike

This is fascinating because we can just do it at home. It feels like making a magic potion… Great stuff!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yep, just… don’t die! XD

LikeLike