Imagine you’re us. You’re looking into the idea that the obesity epidemic is caused, in part or in whole, by some kind of environmental contaminant. The idea already seems pretty strong, but you want to narrow it down to some specific contaminants that might be to blame, so you start putting together a list.

You happen to be aware of a long-running literature that finds correlations between trace levels of lithium in groundwater and public health outcomes, things like lower rates of crime, suicide, and dementia, and decreased mental hospital admissions (meta-analysis, meta-analysis, meta-analysis).

You also know that when lithium is prescribed as a treatment for conditions like bipolar disorder, people often gain weight as a side effect. Based on these two facts alone — lithium causes weight gain at clinical doses, and some clinical effects seem to appear with long-term trace exposure — lithium already seems like the kind of thing that might cause obesity. You add it to the list.

Lots of contaminants on the list don’t survive your scrutiny. When you look into glyphosate (the weed-killing chemical in Roundup), you find lots of evidence against it, and you come away feeling pretty strongly that glyphosate doesn’t cause obesity. Same thing when you look at seed oils.

But the case for lithium keeps getting stronger the longer you look.

You already knew that lithium can cause weight gain at clinical doses, and you know about the literature connecting trace levels of lithium in groundwater to lower rates of things like suicide and homicide rates, suggesting that even the trace levels found in drinking water can have behavioral effects, maybe because of accumulation from long-term exposure. On top of that, you discover that there is one randomized controlled trial examining the effects of trace amounts of lithium, which found that a dose of only 0.4 mg per day of lithium led to reduced aggression, compared to placebo, in a group of former drug users.

You find that many of the professions that are unusually obese — like firefighters, truck drivers, and vehicle mechanics — work closely with heavy machinery, including trucks and cars, that are lubricated with lithium grease. And you notice that the Middle East is one of the most obese regions in the world. This potentially fits because they get a lot of their drinking water from desalinated seawater, which may contain relatively high levels of lithium. And because (as you will later learn) fossil fuel prospecting, especially from arid regions, tends to cause a lot of lithium contamination.

None of this is conclusive, but it seems promising. You start putting out the series A Chemical Hunger, with lithium as one of your three examples of chemicals that might be causing obesity.

Among other things, this leads to some discussion on Reddit. People raise such good points that you decide to review some of their comments in an interlude to the series. There’s a lot worth considering here, but the highlight ends up being a point from u/evocomp, who says:

The famous Pima Indians of Arizona had a tenfold increase in diabetes from 1937 to the 1950s, and then became the most obese population of the world at that time, long before 1980s. Mexican Pimas followed the trend when they modernized too.

This is an excellent point. Sure enough, the Pima in the Gila River Valley of Arizona were unusually obese and had “the highest prevalence of diabetes ever recorded”, way back before the general obesity rate had even broken 10%.

This seems like a real blow to the lithium hypothesis — unless, of course, the Pima were exposed to unusually high levels of lithium way before everyone else.

Turns out, the Pima were exposed to unusually high levels of lithium way before everyone else. For starters, you find this report which says, “In the Gila River Valley, deep petroleum exploration boreholes were drilled during the early 1900’s through the thick layers of gypsum and salty clay found throughout the valley. Although oil was not found, salt brines are now discharging to the land surface through improperly sealed abandoned boreholes, and the local water quality has been degraded.” The report also notes that “lithium is found in the groundwater of the Gila Valley near Safford.” You also find this USGS report, which says a Wolfberry plant “was sampled on lands inhabited by the Pima Indians in Arizona; it contained 1,120 ppm lithium in the dry weight of the plant.” This is an extremely high concentration compared to other plants.

Another USGS report says, “Sievers and Cannon (1974) expressed concern for the health problem of Pima Indians living on the Gila River Indian Reservation in central Arizona because of the anomalously high lithium content in water and in certain of their homegrown foods.”

You track down Sievers & Cannon for more detail. Sure enough, you find that the average concentration of lithium in American municipal waters in 1970 was about 2 ng/mL, while the average concentration of lithium in the water of the Gila River Indian Reservation was about 100 ng/mL, around 50 times higher. Sievers & Cannon also say:

It is tempting to postulate that the lithium intake of Pimas may relate 1) to apparent tranquility and rarity of duodenal ulcer and 2) to relative physical inactivity and high rates of obesity and diabetes mellitus.

This couldn’t possibly have been said with the goal of explaining the obesity epidemic, because the obesity epidemic didn’t exist in the early 1970s when the quote was written. Sievers & Cannon had no idea the obesity epidemic was coming. It was a neutral observation.

If you had to point to some moment as the one we started to believe in the lithium hypothesis, this would be it.

It’s easy enough to come up with a theory that fits all the evidence you’re working with. It’s hard to make a theory that will fit the evidence you’re unaware of. The real test of a theory happens when it comes in contact with something new and relevant. The hypothesis that lithium is responsible for the obesity epidemic makes two predictions (with some allowance for reality being very weird): If some group was exposed to high levels of lithium earlier than everyone else, that group should become especially obese before everyone else did. And conversely, if there’s a group that became unusually obese before everyone else did, that group was probably exposed to unusually high levels of lithium early on. The Pima fulfill these predictions.

As you discover more about the lithium hypothesis, you add more interludes to the series. In the first interlude, you talk more about the possible sources of lithium contamination, like lithium grease, desalinated seawater, and the enormous spills that are a byproduct of fossil fuel prospecting. You also provide a close read of the paper by Sievers & Cannon.

In the second interlude, you take a look at the idea that modern people might be getting exposed to more lithium as a result of drinking from deeper wells made possible by better drilling techniques, and you start making some international comparisons.

Then you decide to try something a little silly. You happened to find a list of the most and least obese cities and communities in America, based on data from Gallup. You think it would be kind of funny to go through each of the cities and communities on the list, and see if you can find out how much lithium is in their drinking water.

This really seems like a long shot. Most cities don’t track the lithium levels in their drinking water, and even if the lithium hypothesis is entirely correct, even if you were able to find some measurements, it’s not clear that the data would show a clear relationship. After all, communities can have more than one source of drinking water, and drinking water isn’t people’s only source of exposure.

But the project unexpectedly turns out to be a huge success. You discover that the leanest communities tend to get their water from isolated reservoirs or pristine mountain snowmelt. Sometimes you can even find official measurements that confirm low concentrations of lithium. The most obese communities, meanwhile, tend to be drawing from aquifers with high levels of lithium, or directly downstream of coal ash ponds that are confirmed to be leaching lithium into the groundwater, or downstream of a lithium grease plant that recently exploded.

All this seems like pretty strong evidence in favor of the lithium hypothesis. A critic would have to argue that unusually obese cities just happen to be downstream from lithium grease plants that experience catastrophic failures. This happened not once, but twice. What are the odds of that, exactly?

A few months later, you get an email from JP Callaghan, an MD/PhD student at a large Northeast research university and specialist in protein statistical mechanics, modeling, and lithium pharmacokinetics. It’s hard to briefly sum up this wide-ranging conversation, but JP agrees that the lithium hypothesis is plausible and discusses some perspectives like bolus-dose exposure and multiple-compartment models that, taken together, suggest that if you’re exposed to small doses over a long enough span, it might even be possible to end up with internal lithium levels as high as those achieved with clinical treatment.

This still assumes that to gain weight, you need to end up with a clinical-level dose in your brain. But the trace exposure literature makes you think that even small doses have some effects. To test this, you survey people who take much smaller doses of lithium as a nootropic, and find that people who take doses as small as 1 mg/day report feeling all kinds of different effects, some of them quite negative. This suggests you may not need big, clinical doses of 50+ mg/day to gain weight, especially if you are exposed to low doses for a very long time.

Of course, 1 mg/day is still more lithium than most people are getting from their water. But you know that people get at least some lithium from their food. Remember how the Pima were eating wolfberries that contained 1,120 ppm lithium, which works out to like 15 mg per tablespoon of wolfberry jam?

You wonder how modern food compares, so you do a literature review. You find good evidence that there’s lithium in modern food, and especially high concentrations in certain foods like meat and eggs. You do another literature review looking at the fact that different sources report very different concentrations of lithium in modern foods. You find that the different papers use different analytical techniques, which may explain why they get such different results.

You test this idea by running an actual study to compare the different analytical techniques. Lo and behold, you find that exactly as you predicted, some techniques almost never detect any lithium in food, while other techniques detect it easily. The second set of techniques are almost certainly the more accurate ones, since they give consistently different readings for different foods, while the other techniques indiscriminately return almost nothing but zeroes.

Looking at the results themselves, you see that some of the foods you tested contain markedly high levels of lithium. In this sample, the highest levels were detected in ground beef (up to 5.8 mg/kg lithium), corn syrup (up to 8.1 mg/kg lithium), goji berries (up to 14.8 mg/kg lithium), and eggs (up to 15.8 mg/kg lithium).

You decide to do a followup study to take a closer look at those eggs. The results confirm your original findings — nearly all the samples contain detectable levels of lithium, and around 60% of samples contain more than 1 mg/kg lithium (fresh weight). As before, the egg samples with the highest concentrations of lithium contain just over 15 mg/kg in the fresh weight.

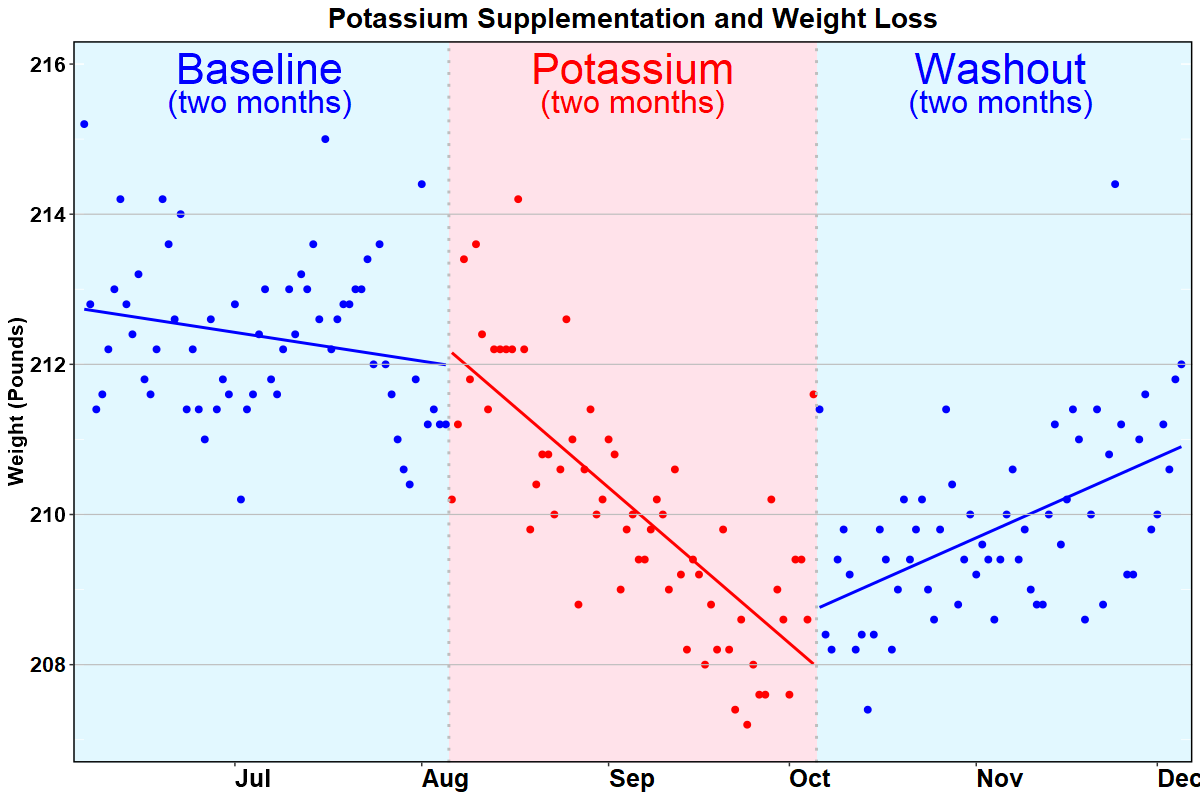

Another hint is that high enough doses of potassium seem to sometimes cause weight loss (though perhaps only under just the right circumstances). People clearly lose weight on the potato diet, and certainly the potato diet provides huge doses of potassium. On top of that, people who took small doses of potassium in solution lost a small but statistically significant amount of weight. And there are the case studies from Krinn, who lost a lot of weight while supplementing potassium, and from Alex C., who lost a smaller but appreciable amount.

This also seems like some evidence for the lithium hypothesis. Potassium and lithium are both alkali metals, and it’s already well-established that sodium interferes with lithium kinetics in the body, so much so that going on a low-sodium diet while taking clinical doses of lithium can be very dangerous. It’s plausible that potassium has similar interactions.

Correlational Analysis

People often ask us, what’s the correlation between obesity and lithium in drinking water? Honestly, we find this question a little confusing.

First of all, everyone knows that correlation doesn’t imply causation. If you discovered a correlation between lithium in town drinking water and obesity in those towns, that would be slightly more evidence that lithium causes obesity, but by itself a correlation isn’t very strong evidence of a causal relationship.

Second, as we described in Section IV of A Chemical Hunger, a small correlation, or even no correlation at all, isn’t evidence of no relationship. Even when there’s a real relationship between two things, there are lots of things that can make it look like there’s no correlation; one example is that looking at a truncated range almost always makes a correlation look smaller than it really is. If you were to look at correlations in lithium exposure, you should expect to be looking at a somewhat truncated range, so the correlation in the data would be smaller than the real relationship, which could be misleading.

This is why we don’t really care about the correlation, because it couldn’t clear things up one way or another. A strong correlation between lithium in water and obesity rates wouldn’t be particularly convincing evidence in favor of the hypothesis. And a weak correlation, or even no correlation, wouldn’t be particularly convincing evidence against. Since it doesn’t clarify either way, you can see why we think that going after these data would be a waste of time.

What would be convincing is experimental evidence, if we could get it. (Though this isn’t always possible; for example, the smoking-lung cancer relationship was established without any human experiments.) We don’t understand why correlation comes up so often. People should remember their hierarchy of evidence.

In general we think this question reveals a misunderstanding about what correlation really is. A correlation is just a mathematical way of describing a relationship, and not even a very sophisticated one. The relationship is what we’re really interested in, and we already have good reason to believe that this relationship is pretty strong — all the evidence we laid out above. In our first post on lithium, in our second post on lithium, in our post on groundwater contamination and historical/international levels, and in our post looking at the fattest and leanest communities in America, we very reliably found that places exposed to high levels of lithium had high rates of obesity, and places exposed to low levels of lithium had low rates of obesity. This is strong evidence for a relationship, even if that relationship can’t immediately be expressed as a correlation.

All this to say, we can give you a correlation coefficient, but we don’t want you to take it very seriously. It does (spoiler) come out in favor of the hypothesis that lithium exposure causes obesity. However, for all the reasons we outlined above, it is not actually strong additional evidence, just one more small item to add to the pile.

Yes, it is a strong positive correlation. No, that is not conclusive, you need to weigh it in the balance with all the other evidence. Do not turn off your brain when you see the scatterplots.

To calculate a correlation coefficient, you need cases where you can find a number for both the obesity rate, and for lithium exposure. In many cases we can’t get one of these numbers (how obese was Texas in 1970? no one knows) or can’t get a specific number, even though observations are in line with the theory (drinking water in Chilean towns can contain up to 700 ng/mL lithium, but how much is it on average?).

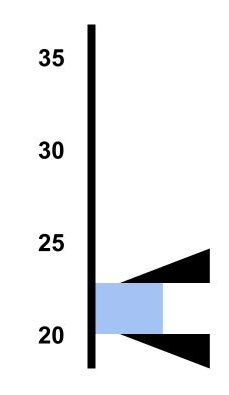

But when we look at the 15 cases where we can give specific values to both variables (the American cities of Denver, San Jose, Barnstable, Miami, DC, McAllen, and San Antonio circa 2010-2020; plus measurements from Greece, Italy, Denmark, Austria, Kyushu Japan, 1964 America, 2021 America, and the Pima in 1973), the scatterplot looks like this:

That correlation is r(13) = 0.744, p = 0.002, with a 95 percent confidence interval of [0.374, 0.910].

The shape is pretty reminiscent of a standard dose-response curve, but it could also indicate a logarithmic relationship; if you log-transform the lithium dosage, it looks very linear:

That correlation is r(13) = 0.732, p = 0.002, 95 percent confidence interval [0.351, 0.905].

This can’t be cherrypicked because those are all 15 cases we are aware of where we have a measurement for both the obesity rate and the level of lithium in local drinking water. If you are aware of other cases, let us know and we will add them to the scatterplot.

There are only 15 datapoints. But at the same time, the correlation is clearly significant, p = .002, even with different models.

Pace Deniers

Some people seem to think we have an axe to grind about lithium, but we’re not sure where this perception came from. At the start we took lithium no more seriously than any other candidate. Over time, we found the evidence compelling, and now we think the case in favor of lithium is quite strong. This is all very carefully documented in A Chemical Hunger and our posts ever since. You can see every step of the process.

Clinical doses of lithium cause weight gain. Not for everyone, but it’s a known side effect. Many effects of lithium probably kick in at trace doses, especially when exposure is long-term. This is probably because lithium accumulates in the body, in the thyroid and/or brain (though possibly somewhere else, like the bones).

Lithium levels in US drinking water have been increasing for at least 60 years. We know where it’s coming from: increasing use of lithium grease, from industrial applications, and from contamination from fossil fuel prospecting, which produces brines known to be enormously rich in lithium.

Populations that were exposed to modern levels of lithium in their drinking water decades before everyone else had modern levels of obesity decades before everyone else. Many of the professions that are especially obese are professions that are regularly exposed to lithium grease.

Most of the leanest communities in America are places where lithium levels in the drinking water are either plausibly low given circumstances (e.g. they get their water directly from pristine snowmelt) or confirmed low by measurement. Most of the heaviest communities in America are places where lithium levels in the drinking water are either confirmed high by measurement or plausibly high given circumstances (e.g. they are directly downstream from a lithium grease plant that recently exploded).

It would be hard for this argument to be any simpler. Honestly, we keep feeling like we’re in the mental gymnastics meme:

We couldn’t fill out the other half of the meme because we honestly can’t tell what deniers are thinking? If you are a lithium denier, please fill out the other half and @ us on twitter.

Lithium Hypothesis for Dummies

To help make this discussion easier, in the following sections we break down the argument in favor of the lithium hypothesis piece by piece.

We invite people to dispute this case. It would be great to hear counterarguments!

We want to make it REALLY EASY for people to engage with the hypothesis, which is why we went to the trouble of writing this post.

However, we have conditions.

If you want to argue, we charge you to either: 1) make the case that these premises are wrong, or 2) make the case that the inferences don’t follow from the premises.

Anything else is pointless griping, and shows a serious lack of reading comprehension, to respond to a hallucinated version of the hypothesis rather than to what we have actually written. We won’t respond to such “arguments”. If we haven’t responded to you in the past, it’s because you displayed reading comprehension levels so low that we couldn’t find a productive way to engage.

As Zhuangzi (Kjellberg translation, p. 218) explains:

Making a point to show that a point is not a point is not as good as making a nonpoint to show that a point is not a point. Using a horse to show that a horse is not a horse is not as good as using a nonhorse to show that a horse is not a horse. Heaven and earth are one point, the ten thousand things are one horse.

Doses

For background, let’s talk about lithium doses.

In clinical settings, lithium is usually prescribed as lithium carbonate, and doses are given in milligrams (mg) lithium carbonate. However, lithium carbonate is 81.3% carbonate and only 18.7% elemental lithium, so the dose of lithium is much lower than the prescribed dose. For example, if you are prescribed 600 mg of lithium 2 times a day, that’s 1200 mg of lithium carbonate, which works out to about 224 mg of elemental lithium.

To keep things standard, and to focus on the actual effective dose, numbers from here on are always elemental lithium.

- Clinical doses of lithium are usually between 336 mg/day and 56 mg/day. However, in rare cases lithium is prescribed at doses as low as 28 mg/day (e.g. here and here), suggesting there may be therapeutic effects at doses this low.

- Doses between 50 mg/day and 1 mg/day we will refer to as subclinical doses, since they are smaller than the usual clinical dose, but still appreciable amounts.

- Doses of less than 1 mg/day will be called trace doses, since you are unlikely to get more than this from your drinking water alone.

Premises

To the best of our knowledge, the following premises are all well-supported. However, some of these premises have more evidence behind them than others.

Premises about Effects and Doses of Lithium

- D1: Clinical doses of lithium act as a mood stabilizer and sedative, and cause all kinds of nonspecific adverse effects, ranging from “confusion” and “dry mouth” to “vision problems” and “twisting movements of the body”.

- D2: When people take clinical doses of lithium, many of them gain weight. As one point of reference, this review paper says, “lithium maintenance therapy stimulates weight gains of over 10 kg in 20% of patients.”

- D3: In a study of Reddit users who had tried lithium as a supplement (supposedly it improves mood and reduces stress), people reported many kinds of effects when taking subclinical doses of lithium. The 10 most commonly reported effects were: increased calm, improved mood, improved sleep, increased clarity / focus, brain fog, “confusion, poor memory, or lack of awareness”, increased thirst, frequent urination, decreased libido, and fatigue. Of the symptoms included, the only three that no one reported were fainting, slow heartbeat, and tooth pain.

- D4: A long-running epidemiological literature (meta-analysis, meta-analysis, meta-analysis) suggests that long-term exposure to trace levels of lithium in drinking water decreases crime, reduces suicide rates, reduces rates of dementia, and decreases mental hospital admissions.

- D5: One randomized controlled trial found that a dose of only 0.4 mg/day improved the mood of a group of violent former drug users, compared to placebo. As far as we know, there are no other RCTs on lithium exposure below clinical levels.

Premises about Lithium Contamination and Exposure

- C1: Between 1962 and 2021, median lithium levels in American drinking water increased by a factor of about 3-4, from a median of about 2 ng/mL to a median of about 6-8 ng/mL. Maximum recorded levels in drinking water increased by a factor of around 10, from a maximum recorded level of 170 ng/mL in 1962 to a maximum recorded level of 1,700 ng/mL in modern data.

- C2: The EPA has expressed concern about trace doses of lithium in American drinking water. In 2021 they put out a report stating, “45% of public-supply wells and about 37% of U.S. domestic supply wells have concentrations of lithium that could present a potential human-health risk.” Specifically, they’re concerned that many water supplies contain more lithium than the relatively low trace benchmarks of 10 ng/mL and 60 ng/mL.

- C3: Naturally you are wondering where all this lithium is coming from. The simplest answer is “human activity”. We started producing appreciable amounts of lithium around the 1950s and we produce and use more and more lithium all the time.

- C4: Lithium grease was invented in the 1940s and was first patented in 1942. Since then it has become the most widely used type of grease, commonly applied to all kinds of machinery in automotive, industrial, and household applications.

- C5: On average, deeper aquifers contain more lithium.

- C6: While basic well-drilling technology as invented in the early 1800s, and the first roller cone drill bit was patented in 1909, portable drills available to homeowners didn’t became effective until the 1940s, and drilled wells didn’t become common for individual homes until the 1970s.

- C7: Large amounts of lithium are found in coal, and thus in coal ash. Oilfield brines or “produced water” generated as a byproduct of oil and natural gas prospecting often contain enormous concentrations of lithium. Lithium concentrations are generally higher in oilfields located in arid regions.

- C8: Millions of gallons of oilfield brines both accidentally and intentionally make their way into the environment as a result of leaks and spills, in thousands of separate incidents every year. Sometimes these spills reach municipal water systems.

- C9: Millions of gallons of oilfield brines are intentionally spread on roads every year, as a de-icer in the winter and for dust control in summer.

- C10: The US currently produces more oil than any other nation, and has been in the top 5 oil producers for a long time.

- C11: Oilfield brines are intentionally used to irrigate crops intended for human consumption.

Premises about the Obesity Epidemic

- O1: Some professions are much more obese than others. For example, the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries survey of more than 37,000 workers found that truck drivers were the most obese group of all, at 38.6%, and mechanics were #5 at 28.9% obese, while only 20.1% of food preparation workers were obese, and only 19.9% of construction workers. Another source, the National Health Interview Survey Data, (2004-2011) found that motor vehicle operators, health care support workers, transportation and material moving workers, protective service workers, and “other construction and related workers” had some of the highest rates of obesity.

- O2: The Pima people, sometimes called Pima Indians, are a group of Native Americans from the area that is now southern Arizona and northwestern Mexico. In the United States, they are particularly associated with the Gila River Valley. The Pima seem to have had normal rates of diabetes and obesity in 1937, but by 1950 rates of both had increased enormously, and by 1965 the Arizona Pima Indians had “the highest prevalence of diabetes ever recorded.”

- O3: In the early 1970s, Sievers & Cannon found that the median lithium level in the Pima’s drinking water was around 100 ng/mL, 50 times higher than the median level of lithium in US public water supplies at the time, which was just 2.0 ng/mL

- O4: In addition, Sievers & Cannon found an “extraordinary lithium content of 1120 ppm” in the local wolfberries, which the Pima “used occasionally for jelly”.

- O5: Lithium contamination in the Gila River Valley likely came from fossil fuel prospecting. This report says, “In the Gila River Valley, deep petroleum exploration boreholes were drilled during the early 1900’s through the thick layers of gypsum and salty clay found throughout the valley. Although oil was not found, salt brines are now discharging to the land surface through improperly sealed abandoned boreholes, and the local water quality has been degraded.”

Premises about Lithium Concentration in Food

Primary Inferences

- K1 – From D1, D3: Some of the known effects of lithium that appear when someone takes clinical doses also kick in at subclinical doses.

- K2 – From D1, D4, D5, O3: Some of the known effects of lithium that appear when someone takes clinical doses also kick in at trace doses.

- K3 – From C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C7, C8, C9, C10, C11, O3, O5: Lithium contamination in the United States has increased since 1962 as a result of human activity, especially fossil fuel prospecting.

- K4 – From F1, F2, F3, C11, O3, O4: Lithium concentrates in certain foods.

- K5 – From O1, O2, O3, O4, O5, C4: Specific populations who have been exposed to high levels of lithium have high levels of obesity.

Secondary Inferences

- S1 – From D2, K1, K5: Exposure to subclinical doses of lithium causes weight gain.

- S2 – From D2, D4, K2, K5: Long-term exposure to trace doses of lithium causes weight gain.

- S3 – From C1, C2, O2, O3, O5, K3: People are regularly exposed to trace doses of lithium in their drinking water, especially people in areas with notable fossil fuel prospecting like the US and the Middle East.

- S4 – From C11, O4, K4: People are regularly exposed to subclinical doses of lithium in their food, especially people who eat food grown in areas with notable fossil fuel prospecting like the US.

Tertiary Inferences

- From S2, S3, C7: The US and Middle East are so unusually obese because they are both arid regions that produce a lot of fossil fuels, leading to relatively high levels of lithium in the local environment.

- From S1, S4: The US is a net food exporter, this is why the world in general is becoming more obese.

Predictions

No prediction can be entirely decisive, but here are some predictions that are likely to be true if the arguments above are sound, and lithium is a major cause of modern obesity rates:

- International variation in obesity rates can be predicted by how much fossil fuels the country produces (not counting sources of fossil fuel that are not concomitant with lithium or that are in locations where they won’t expose people to lithium, e.g. offshore) and how much food they import from the US. International variation is also partially genetic, so even if this is a good fit, it won’t explain anywhere near 100% of the variance between nations. We explore this idea a bit in this post.

- If someone makes a dataset of US counties that includes a “height in watershed” variable, that variable will be more strongly related to obesity rates than a raw altitude variable. If someone can somehow make a “downstream of how much fossil fuel activity” estimate variable, that variable will match even better.

Remaining Questions

Assuming lithium causes obesity,

- How big of a dose is needed to make most people obese? And where is that lithium exposure coming from? Here are three possible (but not exhaustive) scenarios:

- Trace doses of lithium are sufficient to cause obesity. Lithium is cleared from the brain so slowly (see e.g. this paper, “lithium has an increased affinity to thyroid tissue … [investigations reveal] the lithium elimination from brain tissue to be slow”) that over a long enough timespan, even very small doses accumulate.

- Many people become obese on subclinical doses alone, so the subclinical doses of lithium found in food are sufficient to cause obesity. Trace levels in water have a small impact because they provide a more constant dose that keep levels stable, but wouldn’t be able to cause obesity on their own.

- Subclinical doses of lithium by themselves are not enough to cause obesity. However, some foods contain more lithium than others. Sometimes you get unlucky and eat foods with such a high concentration they give you a bolus containing a small clinical dose, which over time leads to serious accumulation. Eventually lithium in the brain reaches the same levels as you would see on clinical doses.

- We know that some plants concentrate lithium in their soil and/or water. Of the crops we grow for food, which concentrate lithium? What’s the rate of concentration — 2x, 10x, 100x? For various levels of lithium in soil and/or water, how much lithium ends up in various parts of the plant? What other factors influence this concentration? Similarly, how much do animals concentrate lithium in their feed into the animal products we eat?

- How do we treat obesity caused by lithium exposure? Is it enough for someone to eat a low-lithium diet? Or do you need to take measures to increase the clearance of lithium from your system? What measures can accomplish that?

- What percent of the obesity epidemic is caused by lithium exposure? 100%? 20%? Something in between? What else, if anything, is causing such high rates of obesity?

- In general, what are the best methods to remove lithium from soil and water supplies?

Alternatives

Some of you may still prefer alternative theories. That is ok.

However, we do want to emphasize that alternative theories should be able to explain the following:

- The unusual relationship between altitude and obesity rates in the United States. We say “unusual” because while many people want to pin this on something immediately related to altitude (like the idea that lower oxygen levels at high altitudes cause lower weights), this doesn’t actually match the evidence. First of all, the paper that people generally point to in support of this idea, Lippl et al. (2010), is quite bad. Weight loss was minimal, the analysis looks p-hacked (or at least suffers from multiple comparisons issues), and the study isn’t even an experiment, there is no control group. On top of that, since they manipulate altitude rather than manipulating oxygen directly, so this is at best evidence that altitude causes weight loss, not evidence for any particular mechanism. No points for presenting a paper that finds evidence for the premise trying to be explained, rather than trying to explain it. As for other arguments, Scott Alexander looked at the case in 2016 and concluded that the atmosphere probably doesn’t cause obesity. Also, simple elevation theories don’t actually match the evidence. Low-altitude states like Massachusetts and Florida are relatively lean, and West Virginia is relatively obese. In our opinion, the pattern matches “length of watershed” better than altitude itself (Massachusetts is very low-altitude but also in a very short watershed), and “aggregate drinking water exposure to fossil fuels” even better (West Virginia is high-altitude and near the top of its watershed but also the site of lots of fossil fuel activity).

- Why the Pima were so obese so early on.

- Why some professions are so much more obese than other professions, and why those particular professions are so unusually lean or obese.

- Why Toledo, OH is so unusually obese and Bridgeport, CT is so unusually lean. Why Green Bay, WI is more obese than St. Paul, WI. Why Bellingham, WA is only 18.7% obese while Yakima, WA is 35.7% obese. In general, why the most obese cities and communities are so obese and the least obese cities and communities are so comparatively lean.

The lithium hypothesis does a pretty good job explaining all of these observations. As far as we know, no other hypotheses of the obesity epidemic can be squared with them. It’s not like they have seed oils in Charleston, WV and not in Charlottesville, VA. It’s not like food is more palatable when placed in front of auto mechanics than when served to other professions. These are rather strong relationships and they need to be explained.

To be completely fair, there are some similar questions that the lithium hypothesis has yet to explain. Here they are:

Finally

And if you want to learn even more, we strongly encourage you to read: